When World War I ended, the German Air Force was disbanded under the

Treaty of Versailles, which required the German government to abandon all

military aviation by October 1, 1919. However, by 1922, it was legal for

Germany to design and manufacture commercial aircraft, and one of the first

modern medium bombers to emerge from this process was the Heinkel He

111, the first prototype of which an enlarged, twin-engine version of

the single-engine mail-liaison He 70, which set 8 world speed records in 1933

flew in February of 1935. The second prototype, the He 111 V2,

had shorter wings and was the first civil transport prototype, capable of

carrying 10 passengers and mail. The third prototype, He 111 V3 also

had shorter wings and was the first true bomber prototype. Six He

111 C series airliners were derived from the fourth prototype,

the He 111 V4, and went into service with Lufthansa in 1936,

powered by a variety of engines, including BMW 132 radials. The first

production models had the classic stepped windshield and an elliptical wing,

which the designers, Siegfried and Walter Gunter, favored. As a military

aircraft, it took longer to gain favor, because military load requirements and

underpowered engines kept its cruising speed down to less than 170 mph.

However, in early 1936, the plane was given 1,000 hp Daimler Benz DB 600A

engines which improved performance dramatically enough to bring in substantial

orders. The first two mass-production versions, He 111 E and He

111 F experienced great success during the Spanish Civil War,

where they served with the Condor Legion as fast bombers, able to outrun many

of the fighters sent against them.

The twin engine Heinkel bomber touched down on the icy

runway. At minus 20 degrees Celsius and with the wind howling at 30MPH, it was

a huge effort for the beleaguered ground crew just to unload the

bomber-turned-transport. Capable of carrying over two tons of bombs, this day

the Heinkel He 111 was laden with ammunition, food, and medical supplies for

the German Sixth Army.

Pitomnik

airstrip, in German Stalingrad pocket, early January, 1943. (2)

In fact, the experience in

Spain generated a false sense of security in which the Germans thought that the

He 111's light armament and speed would be sufficient in the coming war. Thus,

although it was out of date, the large numbers in which it had been produced

made the He 111 the Luftwaffe's primary bomber for far too long in the war,

availability being more persuasive than practicality for this serviceable, but

highly vulnerable, aircraft. Modern fighters like the Supermarine Spitfire and

the Hawker Hurricane proved the He 111's inadequacy during the Battle of

Britain. As soon as possible, the Luftwaffe replaced the Heinkel with the Junkers

Ju 88, reassigning the Heinkel to night operations and other specialized tasks

until, by war's end, it was being used primarily as a transport.

More than 7,300 had been built for the Luftwaffe by autumn, 1944, with another 236 (He 111H) being built by the Spanish manufacturer, CASA, during and after the war (as the CASA 2.111), some with the traditional Jumo 211 engines, some with Rolls-Royce Merlins. In service with the Luftwaffe from 1937 to 1945, the Heinkels remained in Spanish service until 1965. One of the more bizarre adaptations of the Heinkel by the Luftwaffe was the He 111 Z-1, in which two He 111s were joined at the wing with a special section containing a fifth engine. Two prototypes and 10 production models were manufactured, their purpose being to provide the power to haul the huge Messerschmitt Me 321 transport gliders.

More than 7,300 had been built for the Luftwaffe by autumn, 1944, with another 236 (He 111H) being built by the Spanish manufacturer, CASA, during and after the war (as the CASA 2.111), some with the traditional Jumo 211 engines, some with Rolls-Royce Merlins. In service with the Luftwaffe from 1937 to 1945, the Heinkels remained in Spanish service until 1965. One of the more bizarre adaptations of the Heinkel by the Luftwaffe was the He 111 Z-1, in which two He 111s were joined at the wing with a special section containing a fifth engine. Two prototypes and 10 production models were manufactured, their purpose being to provide the power to haul the huge Messerschmitt Me 321 transport gliders.

Production of the Heinkel continued after the war as the

Spanish-built CASA 2.111. Spain received a batch of He 111H-16s in 1943

along with an agreement to licence-build Spanish versions. Its airframe was

produced in Spain he Heinkel He 111 was a German

aircraft designed by Siegfried and Walter Günter at Heinkel Flugzeugwerke

in the early 1930s. It has sometimes been described as a "wolf in sheep's

clothing"[3][4] because it masqueraded as a cargo plane though its actual purpose

was to provide the nascent Luftwaffe with a fast medium bomber.

(Germany had been prohibited by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles from

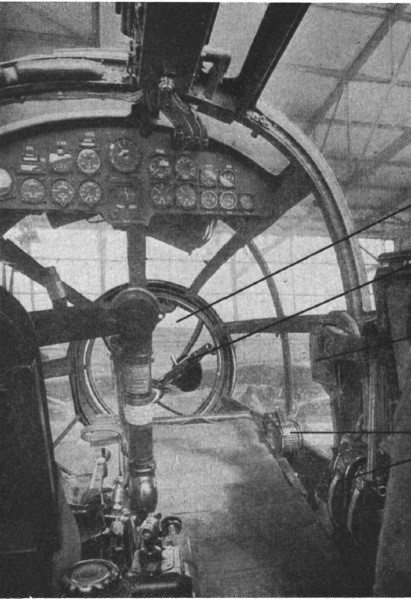

having an air force.) Perhaps the best-recognised German bomber due to the distinctive, extensively

glazed "greenhouse" nose of later versions — in effect, a

"stepless cockpit", with no separate windscreen panels for the pilot

and co-pilot apart from the streamlined shape — the Heinkel He 111 was the most

numerous and the primary Luftwaffe bomber during the early stages of World War

II. It fared well until the Battle of Britain, when its weak defensive

armament, relatively low speed, and poor manoeuvrability were exposed.[4] Nevertheless,

it proved capable of sustaining heavy damage and remaining airborne. As the war

progressed, the He 111 was used in a variety of roles on every front in

the European theatre. It was used as a strategic bomber during

the Battle of Britain, a torpedo bomber during the Battle of the

Atlantic, and a medium bomber and a transport aircraft on

the Western, Eastern, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and North

African Fronts.

Although

constantly upgraded, the Heinkel He 111 became obsolete during the latter part

of the war. It was intended — along with almost every other twin-engined bomber

in Luftwaffe service — to be replaced by the winning design from the

Luftwaffe's Bomber B design competition project, but the delays and

eventual cancellation of

the project forced the Luftwaffe to continue using the He 111 until the end of

the war. Manufacture ceased in 1944, at which point, piston-engine bomber

production was largely halted in favour of fighter aircraft. With the

German bomber force virtually defunct, the He 111 was used for transport

and logistics. (3)

Design conception

After its defeat in World War I, Germany was banned from operating an air force by the Treaty of Versailles. German re-armament began in the 1930s and was initially kept secret because it violated the Treaty. Therefore, the early development of military bombers was disguised as a development program for civilian transport aircraft. |

| Heinkel He 111 in flight |

In the

early 1930s Ernst Heinkel decided to build the world's fastest

passenger aircraft, a goal met with scepticism by Germany's aircraft industry

and political leadership. Heinkel entrusted development to Siegfried and

Walter Günter, both fairly new to the company and untested.

In June 1933 Albert Kesselring visited

Heinkel's offices. (4) Kesselring was head of the Luftwaffe

Administration Office: at that point Germany did not have a State Aviation

Ministry but only an aviation commissariat, the Luftfahrtkommissariat

(4) Kesselring

was hoping to build a new air force out of the Flying Corps being constructed

in the Reichswehr (4) and

convinced Heinkel to move his factory from Warnemünde to Rostock and

turn it over to mass production with a force of 3,000 employees who would

produce the first He 111. Heinkel began a new design for civil use in response

to new American types that were appearing, the Lockheed 12, Boeing

247 and Douglas DC-2. (4)

The first

single-engined Heinkel He 70 Blitz ("Lightning")

rolled off the line in 1932 and the type immediately started breaking records.

In its normal four-passenger version its speed reached 380 km/h

(230 mph), powered by a 447 kW (600 hp) BMW VI engine. (5) The elliptical

wing that the Günther brothers had already used in the Bäumer

Sausewindsports plane before they joined Heinkel became a feature in this and

many subsequent designs they developed. The design drew the interest of the

Luftwaffe, which was looking for an aircraft with dual bomber/transport

capabilities. (6)

|

|

He 111 H20 Fuselage Structure

|

The He

111 was a twin-engine version of the Blitz, preserving the

elliptical inverted gull wing, small rounded control surfaces and BMW engines,

so that the new design was often called the Doppel-Blitz ("Double

Blitz"). When the Dornier Do 17 displaced the He 70, Heinkel

needed a twin-engine design to match its competitors. (5) Heinkel

spent 200,000 hours developing it. (7) The fuselage length

was extended to just over 17.4 m/57 ft (from 11.7 m/38 ft

4½ in) and wingspan to 22.6 m/74 ft (from

14.6 m/48 ft). (5)

First flight

The first

He 111 flew on 24 February 1935, piloted by chief test pilot Gerhard Nitschke,

who was ordered not to land at the company's factory airfield at

Rostock-Marienehe (today's Rostock-Schmarl neighbourhood), as this was

considered too short, but at the central Erprobungstelle Rechlin test

facility. He ignored these orders and landed back at Marienehe. He said that

the He 111 performed slow manoeuvres well and that there was no danger of

overshooting the runway. (8)(9) Nitschke also praised its high

speed "for the period" and "very good-natured flight and landing

characteristics", stable during cruising, gradual descent and

single-engined flight and having no nose-drop when the undercarriage was

operated. (10) However, during the second test flight Nitschke

revealed there was insufficient longitudinal stability during climb and flight

at full power and the aileron controls required an unsatisfactory amount of

force. (10)

By the

end of 1935, prototypes V2 V4 had been produced under civilian

registrations D-ALIX, D-ALES and D-AHAO. D-ALES became the first prototype of

the He 111 A-1 on 10 January 1936, and received

recognition as the "fastest passenger aircraft in the world", as its

speed exceeded 402 km/h (250 mph). (11)(12) The

design would have achieved a greater total speed had the 1,000 hp DB

600 engine that powered the Messerschitt Bf 109's tenth through

thirteenth prototypes been available. (6) However, Heinkel was

forced initially to use the 650 hp BMW VI liquid-cooled engine.

(9) During

the war, British test pilot Eric Brown evaluated many Luftwaffe

aircraft. Among them was a He 111 H-1 of Kampfgeschwader 26

which was forced to land at the Firth of Forth on 9 February 1940.

Brown described his impression of the He 111s unique greenhouse nose:

The overall impression of space within the

cockpit area and the great degree of visual sighting afforded by the Plexiglas

panelling were regarded as positive factors, with one important provision in

relation to weather conditions. Should either bright sunshine or rainstorms be

encountered, the pilot's visibility could be dangerously compromised either by

glare throwback or lack of good sighting. (13) |

| He111 Nose |

Taxiing

was easy and was only complicated by rain, when the pilot needed to slide back

the window panel and look out to establish direction. On take off, Brown reported

very little "swing" and the aircraft was well balanced. On landing,

Brown noted that approach speed should be above 145 km/h (90 mph) and

should be held until touch down. This was to avoid a tendency by the He 111 to

drop a wing, especially on the port side. (13)

Competition

In the mid-1930s, Dornier Flugzeugwerke and Junkers competed with Heinkel for Ministry of Aviation (German Reichsluftfahrtministerium, abbreviated RLM) contracts. The main competitor to the Heinkel was the Junkers Ju 86. In 1935, comparison trials were undertaken with the He 111. At this point, the Heinkel was equipped with two BMW VI engines while Ju 86A was equipped with two Jumo 205Cs, both of which had 492 kW (660 hp). The He 111 had a slightly heavier takeoff weight of 8,220 kg (18,120 lb) compared to the Ju 86's 8,000 kg (17,640 lb) and the maximum speed of both aircraft was 311 km/h (193 mph). (10) However the Ju 86 had a higher cruising speed of 177 mph (285 km/h), 9 mph (14 km/h) faster than the He 111. This stalemate was altered drastically by the appearance of the DB 600C, which increased the He 111's power by 164 kW (220 hp). (10) The Ministry of Aviation awarded both contracts, and Junkers sped up development and production at a breathtaking pace, but the financial expenditure for the Junkers was huge. In 1934-1935, 3,800,000 RM (4½% of annual turnover) was spent. The Ju 86 appeared at many flight displays all over the world which helped sales to the Ministry of Aviation and abroad. Dornier, which was also competing with their Do 17, and Heinkel were not as successful. However, in production terms, the He 111 dominated with 8,000 examples produced. (10) Just 846 Ju 86s were produced, and the Ju 86's weak performance could not match that of the He 111 . (7)Having dropped out of the race, Junkers concentrated on their Ju 88 design. It would be the He 111 that entered the Luftwaffe as the numerically dominant type at the beginning of the Second World War. (10)

No comments:

Post a Comment